IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 92, No. 3: September 2013

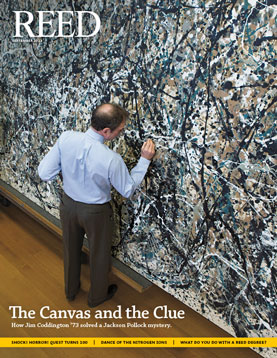

The Canvas and the Clue

Photo by Ruth Fremson/The New York Times

How Jim Coddington ’74 solved a Jackson Pollock mystery.

By Christian Viveros-Faune

For most people, a canvas is a surface on which to paint. But following World War II, a succession of American artists began to treat the canvas, in the words of art critic Harold Rosenberg, as “an arena in which to act.”

One of the most prominent and influential of these abstract expressionists was Jackson Pollock, who became a household name in 1949 when images of him in his Long Island studio landed on the pages of LIFE magazine. Pollock seemed to embody America’s brawny, postwar spirit of innovation, and his untimely death a few years later at the age of 44 while driving a convertible at high speeds along East Hampton’s farm lanes further stoked his biopic-ready renown. It’s no small irony, therefore, that many of Pollock’s half-century-old canvases today depend on just a few low-profile masters for their survival—namely, rare experts like Jim Coddington, the Museum of Modern Art’s chief conservator since 1996.

Art historian Max Friedlander had it right when he said: “Pity the poor restorer. If he does his job well, nobody knows. If he does his job poorly, everybody knows.” Consider the case of Cecilia Giménez. The octogenarian Spanish amateur took it upon herself to restore a century-old Ecce Homo fresco inside Zaragoza’s Sanctuary of Mercy Church in 2012, with disastrous results. Her name is now synonymous with the search words “famous botched restoration” (nearly half a million Google hits at last count), and wags have dubbed the fresco “Ecce Monkey.” No wonder conservators generally prefer anonymity. In the words of the late art historian James Beck, restoration is a lot like having a facelift: “How many times can people go through one without their poor faces looking like an orange peel?”

top: Before treatment; the painting had some deep cracking and was partially filled with gesso.

bottom: After treatment; Coddington and his team retouched such cracks using watercolor paints, not to mask them completely, but to make them less visually prominent.

It was with some trepidation, then—earned through a lifetime of hard-won experience—that Coddington faced the challenge of restoring one of the signal works of postwar American art: the abstract expressionist gem One: Number 31, 1950.

An example of Pollock’s monumental drip paintings, One was completed in summer 1950 while Pollock was at the height of his powers. A virtually priceless treasure—a smaller painting, No. 5, 1948, sold for $140 million in 2006—the painting is one of Pollock’s most ambitious and monumental works. A mural-sized masterpiece in need of expert TLC (the painting measures 9 feet high by 17½ feet across), One makes a unique case for this artist’s enduring importance. In the words of the art critic Robert Hughes, Pollock in the 1940s and ’50s was “the first American artist to influence the course of world art.”

莫

![]()

left: Before treatment; the white passage had been partially obscured by gritty, yellowed overpaint and small splatters of black paint.

right: After treatment; removal of the overpaint reveals hairline cracking but an otherwise undamaged surface.

“E

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago