IRIS login | Reed College home Volume 90, No. 4: December 2011

The New (Olde) Reed Almanac (continued)

House F residents pose with their prize, originally swiped from an Eastmoreland residence.

Doyle owl: Strigidus cementus. Unofficial mascot of Reed College (the official mascot being the griffin (q.v.). While the griffin is a mythical beast, the Doyle Owl is concretely real, although most of the tales of the owl are myths. The original owl was a local piece of garden sculpture, which was carried off as a prank by students living in House F (later renamed Doyle). Since then, there have been many incarnations of the Doyle Owl; the present avatar is owl number 23, plus or minus 11. Almost all of them are made of concrete and weigh over 100 pounds (although there was at least one anti-owl, made of papier-mâché). Contrary to prevalent myth, the Owl was never one of the animals adorning the roof of Old Dorm Block; those are and always have been beavers.

The owl is the paradigm of a trophy, defined by Jay Rosenberg ’63 as “a heavy object of absolutely no intrinsic value whose only purpose is to be possessed and shown by its possessors in public places, without loss of possession.” In the full exercise of the owl tradition, it is painted, shown spectacularly, successfully defended from would-be possessors, and shortly thereafter left unobtrusively but openly to be discovered by a new ownership group.

Most showings have been on campus, although the owl has been documented in settings as far afield as the New York World’s Fair (1939) and the Top of the Mark [Hopkins Hotel, San Francisco]. The solidity of the concrete has been evidenced by a showing at the bottom of a swimming pool, presumably in the San Fernando Valley or possibly Beverly Hills. The owl has been known to spend the occasional quiet weekend at the ski cabin. It has appeared at a campus seder when the door was opened to admit the prophet Elijah. It has substituted for Boris during the Boar’s Head procession of the annual alumni holiday party. It was once displayed in commons, and escaped only after someone cut the electricity and plunged the room into darkness.

Capturing the owl has become increasingly daunting in recent years. Those releasing it back into the wild constantly seek to trump the efforts of their predecessors. This has led to the owl’s being airlifted off campus by helicopter, rising like a specter from the steam tunnels, dangling from a tree whilst being set aflame, and trundling forth from Sallyport encased in a massive block of ice. (This particular incident required the combined efforts of 20 students, a flaming papier mâché decoy, and the strategic use of the walk-in commons freezer.) The resulting owl fight lasted a good seven hours as teams struggled back and forth with the chilly prize, some attempting to defrost it, others simply bent on wrestling the beast into a getaway vehicle as quickly as possible.

The most notable side effect of exposure to the owl is, of course, owl fever—a disease so virulent that it can turn even the most demure Reedies into a howling mob who will stop at nothing to secure their feathered prize. Alumni, faculty, students, staff—all are caught in the inescapable sway of the owl. The question of why a nondescript garden statue from Eastmoreland still inspires such passion remains unanswered.

Doyle, A.E. (1877–1928): Protean architect of Reed’s iconic buildings, including Eliot Hall, Old Dorm Block, the gymnasium (razed), Prexy, the Woodstock language houses, Anna Mann, and commons (now the SU). Despite humble origins and scant formal education, Doyle played a dominant role in shaping the architecture of Portland, particularly at Reed (House F was named after him in 1935). The epitaph set in the south entrance of Eliot Hall describes him well: “Lover and Creator of Beauty.”

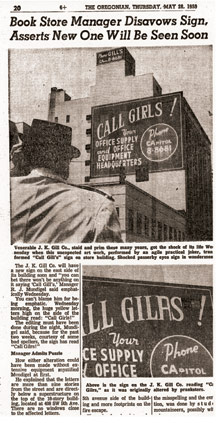

Dyslexia: For many years, the J.K. Gill Company in downtown Portland had a giant sign that read “CALL GILL’S! Your Office Supply and Office Equipment Headquarters.” One night in 1959, Reed students scaled the Gill Building with ropes and converted an “L” into an “R.” Unfortunately, the perpetrator, who was hanging upside down from a rope by one foot, painted over the wrong “L,” resulting in a sign reading “CALL GILRS!” Ensuing press coverage heaped scorn on the Reedies’ inability to spell. Classmates on campus were equally unmerciful; a sign appeared in commons, warning “THE COSP ARE COMING!” Malefactors later braved increased police surveillance of the site to correct their paintographical error. Shortly thereafter, the company modified its sign to read “PHONE GILL’S!”

Economics: The study of a mythical creature known as the Rational Actor—no wonder it is so dismal. Economics became a stand-alone department in 1922. Intriguing courses have included Game Theory; History of Economic Thought; Innovation and Technological Change; and The Economics of Reed College. Influential profs (q.v.) have included Hudson Hastings [1911-20], William Ogburn [1912–17], Clement Akerman [1920–43], Adelbert Friedrich [1921–29], Blair Stewart [1925–49], Arthur Leigh [1945–88], Carl Stevens ’42 [1954–90], George Hay [1956–83], Jeff Parker [1988–], Noelwah Netusil [1990–], Denise Hare [1992–], and Kim Clausing [1996–].

Eliot bug: Scutigera eliotopedia. Arthropod denizen of Eliot Hall, possible relative of the centipede. Legend states that the Eliot bug was the result of a freak accident in the chemistry lab on the fourth floor in the early years of the college. It boasts monstrous antennae, at least 15 pairs of legs, and astonishing bursts of speed as it dashes into dark corners to avoid being called upon in conference.

埃尔

Eliot, T. S.: Obscure vaguely poetical nephew of T.L. Eliot (q.v.).

在

Financial aid: Assistance provided to needy students to offset heartstopping cost of tuition (q.v.). Comes in bewildering variety of grants, loans, and work study, funded by the government and by the college itself. About 52 percent of students currently receive financial aid; average package is $34,200 per year. Reed meets the full need of all continuing students who maintain satisfactory academic progress (six units annually and a GPA of 2.0) even if their family income suddenly collapses. Reed also tries to meet the full need of freshlings and transfers. Each year, however, a small number of applicants are not admitted because the college’s financial aid budget (now about $22.5 million) has been exhausted. If you are outraged by this, please see philanthropy.

Folk dancing: International folk dancing (IFD), or doing dances from many different cultures, became popular at Reed in the ’50s, peaking in the ’60s and ’70s. Originally, the dances of IFD represented major ethnic groups in the United States, with an early dominance of Scandinavia, Germany, Switzerland, Poland, Hungary, Greece, and the British Isles. Later, dances of Israel and the Balkan countries became popular. Begun as a social event, IFD was first taught by the physical education department in 1959, when Pearl Atkinson [P.E. 1959–77] joined the faculty. Pearl nourished IFD, providing opportunities for enthusiastic students to teach specialized dance classes, and beginning a faculty and staff group that continues to this day as the Kyklos Dancers. IFD appeals to Reedies because it combines nativistic styles and movements with an intellectual approach. This spirit was captured in a haiku by Jim Kahan ’64:

Ethnic folk dancers

Unlike urban amateurs

Never need lessons.

佛

Free love: The third part of the trinity that makes up the official unofficial motto of the student body. Adopted as defiant satire sometime in the 1920s, the slogan has been repurposed ever since with varying degrees of irony—irony typically lost on outsiders who only see the T-shirts and shudder. Certainly catchier than the phrase suggested by T.L. Eliot (q.v.) from Matthew 5:15, Ut luceat omnibus (“That it may shine on all”). Try putting that on a T-shirt.

French: The language, culture, and theory of the greatest civilization ever known. Courses over the years have naturally reflected contemporary issues: in 1916, for example, the college offered Soldier’s French. In recent decades, Bill Ray’s classic Introduction to Literary Theory has held enduring appeal. Other intriguing courses have included Masterpieces of the Last Three Centuries, French Drama, French Lyric Poetry, Belgian Literature, Surrealism, and Francophone Literature. Influential profs (q.v.) have included Benjamin Woodbridge [1922–52], Cecilia Tenney [1921–63], Roger Oake [1950-74], Sam Danon [1962–2000], Paul Antal [1968–75], Bill Ray [1972–], Jane McLelland [1974–81], Doris Berkvam [1975–2001]. Gerard Gasarian [1982–89], Hugh Hochman [1999–], Ann Delehanty [2000–], Luc Monnin [2004–], and Catherine Witt [2005–].

German: The language and culture of the greatest civilization ever known. In Reed’s early days, German was for some reason taught alongside Greek under the department of Germanic languages. Intriguing course titles have included Scientific German, Sturm und Drang, Rationalism and Irrationalism, Exile, The Holocaust and the Limits of Representation, and Mythos and the Daemonic. Influential profs (q.v.) have included Charles King [1926–41], Heinz Peters [1940–59], Kaspar Locher [1950–88], Alan Logan [1953–60], Werner Schlotthaus [1960–67], Vincenz Panny [1963–84], Dieter Paetzold [1963–86], Ottomar Rudolf [1963–98], Ülker Gökberk [1986–], Marion Doebeling [1990–97], Katja Garloff [1997–], and Jan Mieszkowski [1997–].

“大酒店”

Grade inflation: Vile phenomenon in which mediocrity marches to the front of the alphabet. Virtually unknown at Reed. The average GPA for Reed students is 3.08 and has scarcely budged in 26 years. In that time, only 10 students have graduated with a perfect 4.00 GPA.

Graduation rate: Reed’s graduation rate was never exactly stellar for a host of reasons, including sunshine deprivation, the grueling workload, and Reedies’ propensity to drop out and pursue their dreams. (Can you say Apple?) In the early ’80s, only 28 percent of students graduated in four years. Since then, the figures have shown dramatic improvement, thanks to a sustained effort to improve student life and boost academic support. Today the four-year rate is 70 percent and the six-year rate 79 percent.

Great Lawn: A vast expanse of green, ideal for dogs, Frisbee, softball, commencement, hot air balloons, physics experiments, and reading Plato. In A.E. Doyle’s original master plan, the lawn was envisioned as a giant grassy quadrangle criss-crossed by walkways and flanked with Gothic buildings.

LATEST COMMENTS

steve-jobs-1976 I knew Steve Jobs when he was on the second floor of Quincy. (Fall...

Utnapishtim - 2 weeks ago

Prof. Mason Drukman [political science 1964–70] This is gold, pure gold. God bless, Prof. Drukman.

puredog - 1 month ago

virginia-davis-1965 Such a good friend & compatriot in the day of Satyricon...

czarchasm - 4 months ago

John Peara Baba 1990 John died of a broken heart from losing his mom and then his...

kodachrome - 7 months ago

Carol Sawyer 1962 Who wrote this obit? I'm writing something about Carol Sawyer...

MsLaurie Pepper - 8 months ago

William W. Wissman MAT 1969 ...and THREE sisters. Sabra, the oldest, Mary, the middle, and...

riclf - 10 months ago